Anna to Annie: Spotlighting women in photographic history.

March 12th, 2022

Exploring photography during Women’s History Month can be a rather complex journey. Focus on the industry pioneers…or the subjects? The obvious topics are “Notable Women Photographers,” and “Women in Photography.” Let’s explore a few from those perspectives.

Anna, Fannie, and Jennie – Early Photo Pioneers

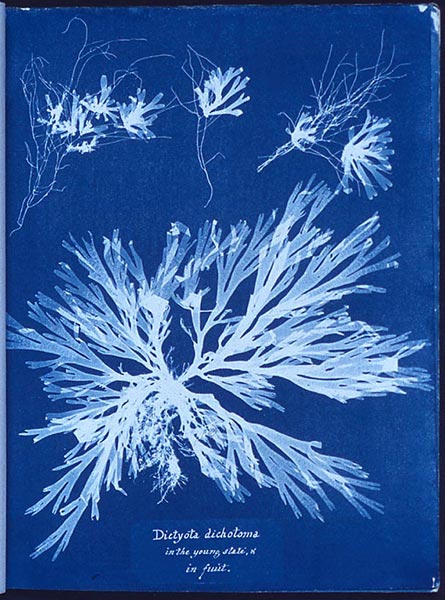

Right between the milestone events of the first camera photograph taken in 1826 by Niépce, and George Eastman creating the film roll in 1889, British Botanist Anna Atkins took up the newly emerging art of photography for more practical purposes. Her studies of various types of British Algae were difficult to record and categorize with arduous drawings.

Anna heard about the “talbotype” photographic process patented by British inventor William Henry Fox Talbot in 1841. That same year, her father wrote to Talbot, “My daughter and I, shall set to work in good earnest ’till we completely succeed in practicing your invaluable process.” Yet, Anna later settled on the cyanotype, a different photographic process developed by her neighbor Sir John Herschel, that produced blue and white prints with sharp contours and the detail she sought for her botanical journaling.

A photographic first

Anna’s book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, was published in 1853, and she is credited as the first person to illustrate a book with photographic images. She then got busy, shifting from algae to ferns and plants, capturing detailed images of stems, leaves and roots. Later that year, Anna published a book of images on these terrestrial subjects, which became her most successful publication. Over the years, Anna’s photography emphasis evolved from scientific to artistic as she focused on creative use of space, color and composition using subjects such as flowers, feathers, and lace.

The New Woman and photographing the famous

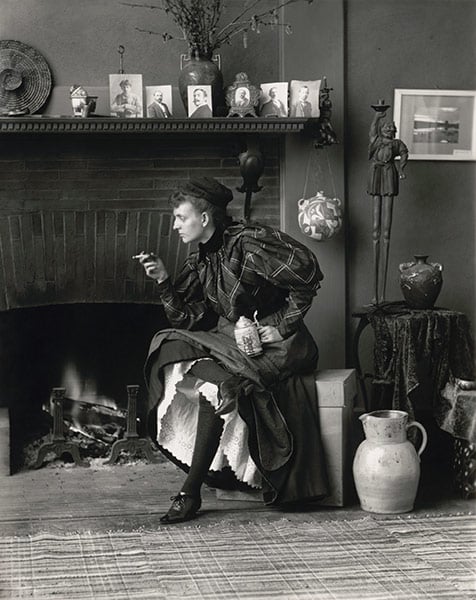

Frances Benjamin Johnston, also known as Fannie, is widely regarded as the first woman to have a long, successful career as a photographer…and maybe even taking the first female “selfies.”

Fannie created two famous self-portraits considered rather rebellious at the time. Her 1896 image, “The New Woman” is provocatively posed with a cigarette in one hand and a beer stein in the other, with her petticoat showing draped over a male-like crossed leg. In another noted self-portrait, Fannie is fully dressed as a man, even with a mustache.

But Johnston’s career as a successful photojournalist is her enduring legacy. She practiced her craft during a prolific period of technical photographic advancements – including the halftone that accelerated the ability to print detailed photos in books and magazines, thereby driving the mass consumption of photography. Fannie’s work and her famous celebrity subjects were widely published, fueling her respect and reputation. Based in her Washington, D.C. studio, she took portraits of five U.S. presidents including Teddy Roosevelt, and such luminaries as Mark Twain, Susan B. Anthony and Booker T. Washington.

Fannie was a strong advocate for women as professional photographers at a time when women’s rights activism was gaining traction. Many women found inspiration from her quote in an 1897 Ladies’ Home Journal article titled What a Woman Can Do with a Camera.

“The woman who makes photography profitable must have, as to personal qualities, good common sense, unlimited patience to carry her through endless failures, equally unlimited tact, good taste, a quick eye, a talent for detail and a genius for hard work. In addition, she needs training, experience, some capital and a field to exploit.”

– Frances Benjamin Johnston

A woman of art, film and photography.

Jane “Jennie” Louise Van Der Zee Toussaint Welcome was known as the “Legendary Harlemite.” Also known as Madame Toussaint, she was the first African American owner of a business in Harlem, which had a mostly white population in the early 1900’s. Jennie and her husband founded The Toussaint Conservatory of Art and Music, an art school and photographic studio in Harlem that influenced the Harlem Renaissances over a 40-year span.

As the silent film era gained popularity, Jennie is credited as one of the only African American women filmmakers at the time, producing films that authentically portrayed the lives and struggles of the people of her race. Her photographic and film work sought to recognize the contributions of African Americans in society, and even in war efforts, as opposed to the stereotypes portrayed in some films of the day. The Toussaint Motion Picture Exchange produced newsreels depicting African American patriotism and contributions in World War I as soldiers fighting in Europe.

In August 1918, Jennie and her husband copyrighted her painting, Charge of the Coloured Divisions, which would be the only painting by a black artist accepted by the US National War Savings Committee to be used as a poster for the Liberty Loans campaign. Even though no copies of the work exist today, the posters and one million postcards printed raised significant funds for the war effort. Jennie’s photographic, film and art contributions were instrumental in the artistic and dignified expression of black subjects at a pivotal time in American history.

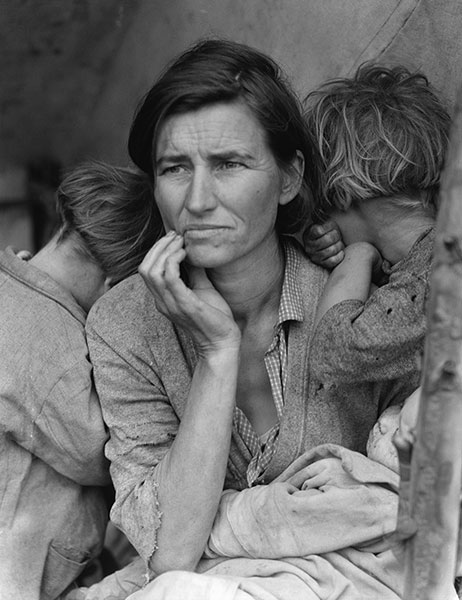

The Migrant Mother That Started a Movement

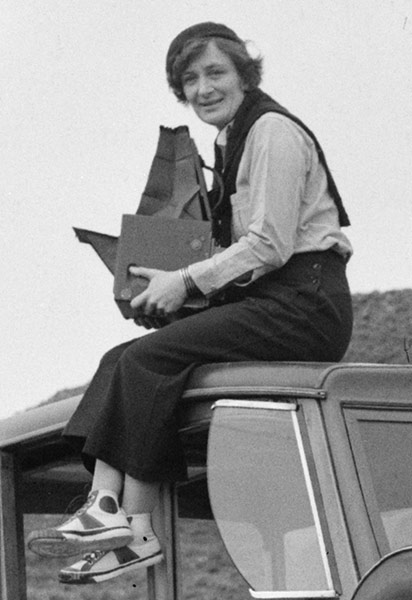

For much of America, the plight of people escaping the ravages of the Dust Bowl and migrating to California was a remote occurrence. However, in 1936 an iconic photo taken by female photographer Dorothea Lange became the personification of the struggle of the migrants to find work and just survive during the Great Depression. The moving photo was first published March 11, 1936, in the San Francisco News, and later widely circulated to magazines and newspapers across the country. The desperation, hunger and hopelessness of migrants, as symbolized in the photo, brought the emotion of the localized experience into every home across the nation.

Dorothea Lange contracted polio at age 7, and her father abandoned the family when she was 12. By the time Dorothea took the photo while employed by the U.S. Farm Security Administration, she had channeled the tragedies of her youth to empathize with many of her photo subjects and honestly portray their emotions and struggles. Of polio, Dorothea said, “It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me.”

Dorothea Lange on shooting the famous photograph.

Dorothea related how the migrant photo was shot, “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction.”

At the time The Migrant Mother image was taken, Dorothea promised the subject, a woman desperately trying to support her six children, that her name would never be published, so as not to embarrass her children. Decades later, this famous anonymous subject was discovered at the age of 75. Florence Owens Thompson was living in a trailer park outside Modesto, California, and was eager to tell her full life story to a reporter for the Modesto Bee.

Margaret, Diane and Annie – Creating a Photo Style

In honoring the women of photography throughout history, three more recent photographers deserve acknowledgement for their pioneering and creative accomplishments, along with their signature styles.

Margaret Bourke-White was the first American female war photojournalist, the first Western photographer allowed to take photos in the Soviet Union during Stalin’s reign, and has the distinction of taking the cover photo on the very first issue of LIFE magazine.

Fortune, Luce and Life.

Born in New York City, Margaret attended the Clarence H. White School of Photography and after graduating in 1927, she began her career in photography by opening a studio in Cleveland, Ohio. Her portfolio of industrial photos attracted the attention of Fortune magazine publisher Henry Luce. In 1930, Luce sent her to the Soviet Union, where she was the first foreign photographer to capture images of Soviet industry. In 1936, Luce hired Bourke-White as a staff photographer for his newly conceived Life magazine, where her Fort Peck Dam photo was featured on the first issue cover.

Margaret is renowned as one of the first female war photographers, recording the German invasion of Moscow in 1941, and was the first woman to fly with crews on bombing missions during World War II. In later years, Margaret captured images of many notable world events, including Gandhi fighting for independence in India, South African conflicts, and the Korean War. After being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, she created her last photo essay, “Megalopolis,” for Life magazine in 1957.

Focusing on inclusiveness in photography

Diane Arbus carved out a reputation as a professional photographer who helped normalize subjects who were often considered on the fringes of society. While most images of the day represented average American families, Diane spotlighted transgender people, along with circus performers and nudists.

Her stark, yet detailed, images focused on the physical differences that set them apart from their present-day standards of beauty. At a time when some of her subjects were considered “repulsive” by many, the innovation of her artistry to reflect their odd beauty was later considered “groundbreaking.” Diane once stated about her work, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.” She also shared that her images were intended to capture, “the space between who someone is and who they think they are.”

Over her career, Diane contributed to Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines. After becoming burned out with commercial work, she took her camera out to the streets of New York, shooting photos of all types of people in society. Today, Arbus is remembered as one of the best known and most controversial women photographers in history, based on the significance of her unsettling and compelling photos.

The rock star of women photographers

Annie Leibovitz is the latter-day rock star of women photographers, famous for her images of actual rock stars and celebrities for Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair. Her extensive portfolio features subjects ranging from Queen Elizabeth II to a very pregnant and nude Demi Moore, to the last photo taken of John Lennon just five hours before his death in 1980.

As a child, Annie took photos during her family vacations and later studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute, intent on teaching art as a career. Inspired by the work of Richard Avedon and Henri-Cartier Bresson, she took night classes in photography and became a photographer at Rolling Stone in 1970 and was quickly named chief photographer at the height of the Rock era. She later moved to Vanity Fair and there cultivated her signature style of lighting, bold colors, and unique posing for portraits that were highly coveted by celebrity subjects.

Annie’s work intimately captures the personality and playfulness of subjects, often becoming iconic or trademark images associated with those who sit for her. Of her work, Annie has said, “I no longer believe that there is such a thing as objectivity. Everyone has a point of view. Some people call it style, but what we’re really talking about is the guts of a photograph. When you trust your point of view, that’s when you start taking pictures.”

Annie Leibovitz was the first woman photographer featured in a solo exhibition in 1991 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Popular among photographers is her 2008 book, Annie Leibovitz at Work, in which she breaks down little-known details about how some of her most famous images were created. Annie’s photographs are curated in collections at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and many other museums and galleries.

The contributions of women photographers and female subjects throughout history are so vast that chronicling them in a single article or publication is virtually impossible. By spotlighting a few pioneers from Anna to Annie, maybe we can all draw inspirations from their exploits and enduring photography.

Stay tuned for part two of this series, where we look at contemporary female photographers who are shaping the industry.